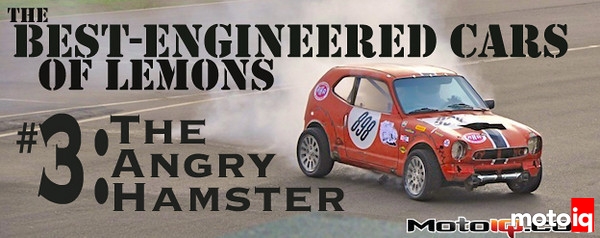

The Best-Engineered Cars of LeMons

#3 – the Angry Hamster Honda Z600

What you are about to see is a ridiculous feat of LeMons engineering. At 1400 lbs and 116 hp, it has nearly the same power/weight ratio as an S2000. It's packaged like a proper race car, with the engine in the middle and the drive wheels in the back. Weight distribution is a dead-even 50/50, an unusual feat for a mid-engine car, and the wheelbase is nearly a foot shorter than a Lotus Elise's. It's powered by a 10,000-rpm V4 engine mated to a 6-speed sequential dog box, and packs a limited slip diff, and 4-wheel discs. And all of it was built under the requisite $500 limit for all LeMons cars.

|

||

| The first step in prepping any LeMons car is to chase out the varmints. |

That last bit appears to be an impossible trick of accounting, but we actually sorta believe it.

The most important ingredient in this formula is Tim Taylor, a sleepless design engineer with the keys to a huge machine shop and a wife suddenly out of town on business for a few months. This is a volatile combination.

Add to this a diminutive 1971 Honda Z600. Actually, diminutive doesn't even begin to capture the size of this car. It's the size of a shoe. This precursor to the Civic was designed before the Japanese discovered food, a time when nobody in the country was over three feet tall. Powered by a 36-hp 2-cylinder, 600cc motorcycle engine, the Z600 is the last thing in the world you'd ever think about racing in a series that allows you to race wheel-to-wheel against a madman in a hearse.

Unless, that is, you're blinded by an engineer's obsession with power-to-weight ratios. At 1,100 pounds, the Z600 is irresistibly light. There also happened to be one sitting in the side yard of a foreclosed house not far from Tim's shop. After a few weeks languishing on Craigslist at $600, the price dropped to $300 and Tim swooped.

|

||

|

This box of parts was sold for more than the cost of the car, bringing the project cost back down to $0. |

Lemons accounting rules, just like real accounting rules, allow you to sell off parts of your car to reduce the total cost. The drivetrain, front suspension, wheels, brakes, and miscellaneous bits netted $410, bringing the cost of the car back down to zero (LeMons rules don't let you go negative, unlike the real world).

Now, what about power?

Since motorcycle power originally motivated the Z600, it doesn't take much imagination to figure out where to look for a new engine. Following the MetroGnome down the path of modern squidbike power seems to be the obvious answer, but the Z600 is so ludicrously tiny an inline-4, even one from a motorcycle, just won't fit.

Finally, Tim turned the clock back a few decades. The Honda Magna VF1100C was, for a brief time in 1983, the fastest motorcycle you could buy. Capable of 11-second quarter miles, the thumping V4 put out almost four times the power of the Z600's original engine, and its unusual shaft drive configuration and narrow V4 layout were a perfect fit for the car.

Other than stunning acceleration, the Magna had little going for it. The bikes were heavy, ill handling turds; kind of like a two-wheeled '78 Camaro. Magna styling has not weathered the test of time, either, so a Magna today is about as desirable as, well, a Honda Z600. Tim grabbed a complete, un-crashed bike from a still-shaking first-time rider for $400. Here's a word of advice if you're thinking of learning to ride a motorcycle: Don't try to learn on a 2-wheeled Camaro.

Undesirable as they may seem, there are still, apparently, enough Magna fans out there that Tim and the gang were able to shine up the seat, tank, forks and a few other bits and sell them one by one. In the end, the bike only cost $65.

Bantamweight car, healthy motorcycle powerplant, the rest should be easy, right? Hardly. Turn the page for the jaw-dropping details.