,

|

| Edmunds Inside Line lost 70whp on the 911 GT2 RS before they directed a pair of small blowers into the air ducts for the intercoolers. |

Yet another difference between testing NA and turbocharged cars specifically is how the dyno loads up the engine. For an NA or supercharged car, it doesn’t really matter how the car is loaded up as once that throttle plate is wide open, that’s the max airflow the engine can take in. For a turbocharged car, the airflow rate depends on how fast the turbo is spinning. To get the turbo to spin up and make boost, there needs to be a load on the car. More load results in more fuel burned and more exhaust energy to spin up the turbo. The turbo is sort of like a self feeding machine; once it starts to spin up, it crams more air into the engine allowing for more fuel to burn. More fuel burnt means more exhaust energy to spin the turbo faster which in turn feeds the engine even more air allowing even more fuel to be burnt. This is most clearly demonstrated when a big turbo is used on a small engine. It very slowly builds boost and once it reaches a threshold, the boost comes up exponentially creating a huge torque gain in a narrow rpm range.

Check out the dyno of this turbo Vespa. lag lag lag lag lag spool boost!

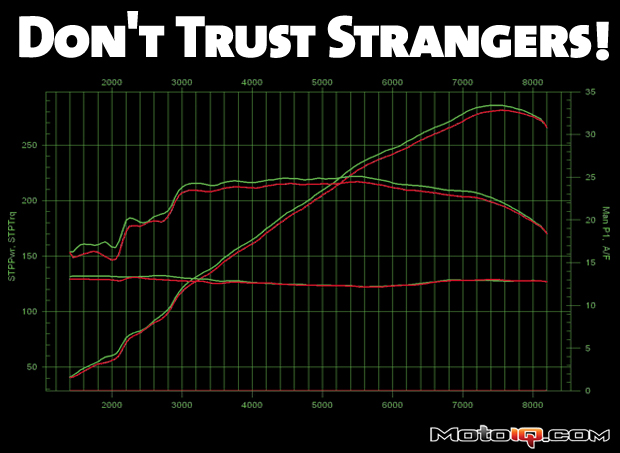

If you own a turbocharged car, the difference in the shape of a boost curve due to loading is easy to illustrate; just do a couple WOT pulls starting from 2k rpms in 2nd gear and 5th gear. The results will be drastically different boost curves versus rpm because 5th gear loads up the engine much harder than 2nd gear.

|

| This is an old datalog of two pulls spliced together from my 2005 Evo. I think the first pull was in 3rd gear and the second pull was in 1st gear. Notice that 3rd gear hits ~240 load at about 3500 rpms whereas in 1st gear, the engine doesn’t hit 240 load until about 4750 rpm. |

How does this behavior relate to dyno results? Well, on an inertial dyno, the gear the car is tested in can significantly alter the shape of the boost, torque, and horsepower curves. Also, differences in dyno types load up the car to varying degrees. Within a dyno type, the way the car is loaded up can also be changed. All these factors means there’s a whole lot of potential variability in dyno results for turbocharged cars.

If there are so many variables that can alter dyno readings, then why do we use dynos? They are still great tuning tools if you eliminate as many variables as possible. Don’t pay much attention to the absolute numbers, only the changes relative to a baseline. If you’re getting your car tuned, pretty much all the variables are eliminated between tuning changes and dyno pulls as long as the weather isn’t changing drastically over the course of the tuning session.

If you’re trying to track changes to your car over a period of time as you add mods, always go to the same dyno; remember that two different dynos of the same model may read differently. If using a chassis dyno where the car is strapped down, always strap the car down the same way with the same amount of force. Also make sure your alignment and tire pressures are the same. If you change your alignment, pressures, tire type, how hard you strap down the car (which can cause changes in toe with toe-in or toe-out causing power losses), or even a new tire vs old tire (differing levels of grip and friction), the readings will have some variance. If you use a Dynapack that attaches to the hubs, all those variables are eliminated. Try to dyno in the same weather conditions as previous tests. If you’re within 10 degrees F, then the correction factor will barely be different. If you dyno one day when it’s 100F and another day when it’s 50F, well, your measurements will not really be comparable.

The moral of the story is that trying to compare dyno numbers from different dynos, locations, and weather conditions for bragging rights is borderline idiotic. The best case for trying to compare chassis dyno numbers between different cars is if both cars were tested on the same dyno in similar weather conditions. Use the dyno as intended, as a tool to measure how vehicle setup changes alter power output. Don’t bench race.